“All those positive aspects together in one novel should ensure an enjoyable read that wraps you up in a wonderful fantasy world. Yet sadly, the positives weren’t enough to make up for one simple gap they all had in common.”

I’m a reader more than an author, and I’ve learned about writing quality through both. Over the last month or so, I’ve read some excellent novels. Some of these otherwise outstanding stories disappointed me where it could be easily avoided, yet I’m shocked to find my opinion that this is of concern is in the minority.

I’m a reader more than an author, and I’ve learned about writing quality through both. Over the last month or so, I’ve read some excellent novels. Some of these otherwise outstanding stories disappointed me where it could be easily avoided, yet I’m shocked to find my opinion that this is of concern is in the minority.

Three specific novels stand out. They varied from a pleasant romance with mild conflict to an excellent “sweeping epic romance” novel with strong dramatic tension throughout, and another that had a mix of sweetness and angst that put it in the middle of the first two. In each case, the plot moved forward at a brisk pace through the trials the protagonists faced with minor villains and/or misunderstandings towards a satisfying Happily Ever After.

The novels were Pride and Prejudice variations, and compliance with canon characterization for the major characters was strong and consistent. A couple of minor characters were given larger roles and personalities, and new characters enhanced the variations, not unusual for Jane Austen Fan Fiction (JAFF), and well done in each case.

Sounds good so far! Read on…

Some tropes were used in one novel, and a subplot seen in another author’s earlier novel was copied in that same novel, but the other two did a fine job of avoiding them. Quotes from Pride and Prejudice were inserted in key places, although in one novel, they were too long and cliché.

But everyone enjoys a hint of the real Austen, right? Read on…

A range of ability to use of point of view was seen in the books. The sweet romance author did an excellent job of maintaining a standard (not deep or close) third person, multiple point of view, taking care to ensure that POV changed by scene. The other two were less successful, awkwardly using multiple techniques and head-hopping. Obviously the latter authors are less disciplined in good POV techniques.

Ouch. But the novel that escaped head-hopping must be the best one, right? Read on…

Much of the language felt authentic and maintained the mood of the Regency era. The light romance novel was bogged down with long sections of narrative and could have used more dialogue; the others were well-balanced. The authors each used a number of non-period words, but I’ve read far worse by well-known prolific JAFF and Regency romance authors. Most of the common anachronisms included by Regency writers were avoided, and scenes were peppered with little touches of period description that helped move the reader’s imagination into another time.

One made a common mistake: rather than ending when the story arc had been completed, the story line digressed into a new plot direction when it should have been tying up loose ends. That wasn’t enough: an epilogue that had nothing to do with the plot line and was of a different style altogether followed. But the other two novels had perfect endings: no loose ends, the timing was neither abrupt nor dragged out, and the reader was satisfied with the romantic outcome.

Okay, a few flaws, but they still sound like good books, right? Read on…

Most authors have at least one weak area in their writing, including those above. Some have continuity or inconsistency problems, so the reader is frequently pulled out of the story to flip back to try to resolve their confusion. Excess elements such as side plots, back story, or redundancy result in boredom. Too many novels have an inadequate premise with minimal conflict and a plot with no complex elements, rushing through predictable circumstances to their happily ever after while rendering the novel forgettable.

Most authors have at least one weak area in their writing, including those above. Some have continuity or inconsistency problems, so the reader is frequently pulled out of the story to flip back to try to resolve their confusion. Excess elements such as side plots, back story, or redundancy result in boredom. Too many novels have an inadequate premise with minimal conflict and a plot with no complex elements, rushing through predictable circumstances to their happily ever after while rendering the novel forgettable.

These three novels escaped those specific problems. The striking situation here was that even with the weak areas noted, the authors were skilled. Weaknesses were not specific to one novel; rather, each had one or two areas to improve upon but excelled for the most part. The novels each had an interesting, unique premise that was well-executed. Dashes of humour enhanced the dramatic themes, and excitement was felt during situations with physical action. Strong romantic themes supported the story arc. One in particular stood out among JAFF Regency novels for excellent story-telling that took the reader’s imagination away.

For a captivating story line, a reader could overlook one or two flaws, right? Read on…

All those positive aspects together in one novel should ensure an enjoyable read that wraps you up in a wonderful fantasy world. Yet sadly, the positives weren’t enough to make up for one simple gap they all had in common.

A lack of proofreading significantly spoiled the final result of what could have been a decent book.

If I were reviewing these novels for Amazon, a full star would be dropped at minimum for the proofreading errors alone. I’m not being trivial over a few minor typos. Plurals using an apostrophe and incorrect plural possessives, made-up spellings of words, homonyms and homophones used incorrectly, missing letters, missing periods at the end of sentences, and missing quotation marks on one end of a character’s dialogue are examples.

A JAFF author once questioned why I liked working with Meryton Press as opposed to self-publishing, and I listed the benefits I get for free, including editing. Her response?

“No one cares about editing. JAFF readers buy everything released and give top reviews no matter what the quality.”

Sadly, she’s right. Whether enchanting or bland, JAFF novels with poor attention to editing routinely get five-star reviews, even when the reviewer mentions the editing was bad! Review blogs never mention proofreading and ignore blatant mistakes, as they’ve rated these three books almost consistently at 4.5 to five stars. It’s disappointing for those of us who go the extra mile.

Many reviewers make exceptions for self-published books, saying poor editing is expected. That must be a disappointing surprise to 80% of self-published JAFF authors* who make that extra effort to put out quality novels for their fans. Readers shouldn’t reward author-publishers who are lazy or cheap any more than traditional publishers who employ editors who don’t know their craft—it’s not fair to those who care about their readers. I paid for the book. I have a right to expectations.

The errors added up, affecting my overall perception of these otherwise good books. The high-angst novel was one of the most entertaining books I’ve ever read, and though the problems were fewer than the other two, it had confusing head-hopping and enough proofreading errors that it was not just a slight omission. In all three novels, clearly no skilled person did a final check for the author.

A smart author won’t stop there. The use of a good general editor (substantial editor, line editor, and/or copy editor) would make these authors look so much more professional. Even those who can manage a good effort at all of the aspects mentioned above will have weak points they don’t see when they read through their work. Another set of eyes, particularly a professional who is experienced at what to watch for, can make an okay novel great.

A smart author won’t stop there. The use of a good general editor (substantial editor, line editor, and/or copy editor) would make these authors look so much more professional. Even those who can manage a good effort at all of the aspects mentioned above will have weak points they don’t see when they read through their work. Another set of eyes, particularly a professional who is experienced at what to watch for, can make an okay novel great.

I have huge appreciation for the beta teams who have assisted me with my unpublished work. Their volunteer, well intentioned, non-professional reviews helped me learn to be a better writer. This is great for JAFF sites such as A Happy Assembly where members with a huge range of writing skills are encouraged to add to the large number of free stories. But if you charge for the book, you’ll be held to a higher standard.

A beta reader, Aunt Sally, an English major, or a teacher can’t take the place of an experienced professional editor. I’ve read JAFF novels written or edited by these supposed experts that had laughable errors. Professional editors are familiar with typical mistakes, the specifics of genre fiction rules, and lots of good alternatives to improve a novel.

Special smooches go to the Meryton Press editors I’ve worked with: Gail Warner and Christina Boyd. Both are caring, kind, fun women. With their unique talents and styles, each brought my writing to a higher level as professional editors. Ellen Pickels is the lady who covers the a55es for all of us as Meryton Press’s final editor. She serves as proofreader, layout editor and graphics editor! After reading the above mentioned novels, the view that she’s worth her weight in gold has been reinforced! Thanks to them all!

I hope authors who read this will know where they fit, and those who care will improve or continue their best practices and be proud of their dedication to their readers’ satisfaction. I also hope those who don’t care will get their just desserts someday, rather than a reward of five stars when they didn’t even try to respect their readers. Wishful thinking, I know.

* My “guesstimate.”

Note: This post has not been professionally edited. If you need a few spare commas, I probably have some to offer!

Next post: The Smart Author Self-Edits: some links to help you improve your craft.

Like this:

Like Loading...

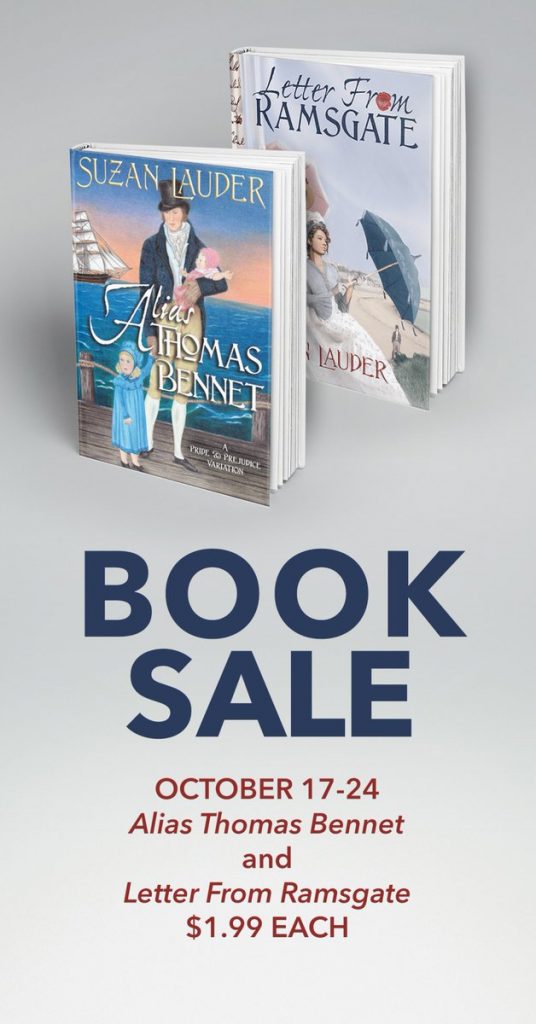

For those who are new to these two books, both are variations of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and have happy endings. Letter from Ramsgate has a great deal of angst, and is suited to all readers mature enough to read and appreciate Pride and Prejudice. Alias Thomas Bennet has a mystery component and is suited to mature readers who are not sensitive to trigger scenes. Both are highly rated by readers, earning Amazon reviews averaging greater than four stars out of five. I myself enjoy re-reading them from time to time!

For those who are new to these two books, both are variations of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and have happy endings. Letter from Ramsgate has a great deal of angst, and is suited to all readers mature enough to read and appreciate Pride and Prejudice. Alias Thomas Bennet has a mystery component and is suited to mature readers who are not sensitive to trigger scenes. Both are highly rated by readers, earning Amazon reviews averaging greater than four stars out of five. I myself enjoy re-reading them from time to time!