Over the last few years, Romance novels have undergone a profound change, where the point of view (POV) within the story is now almost always Third Person Limited, Close, or “Deep POV.” This is hard for some writers who are accustomed to writing in a voice called Omniscient Narrator (ON), which is much easier to tackle and is familiar, especially to older writers, since so much of what we have written during our lives has been impersonal, particularly professional writing.

The up-and-coming New Adult romance genre almost exclusively uses first person POV. This preference is a result of New Adult’s growth out of the Young Adult genre, which uses first person POV a great deal. It also focuses on Deep POV, where the reader is not just being told the story, but the reader’s head is almost inside the narrator’s head.

What does all this mean? Here is a summary of what I’ve learned, with some more of my Learning from My Mistakes rules and external links.

ON versus Third Person Limited

Think of the POV as a camera: if you are writing in ON, you are allowed to see and show everyone’s point of view. In this case, the camera is up high, almost an eagle’s view, showing the entire scene on behalf of all the characters in the story. It can focus on one or more characters, but there’s a catch—the voice is that of the narrator, and not that of the character. That is, the narrator tells the story, expressing the viewpoints of each character.

It’s advisable to limit the number of characters who are “speaking” and to show clearly when that character’s viewpoint is over. Otherwise, the story winds up having a condition known as “head-hopping” where the reader can become confused as to who is having these particular thoughts.

Suzan Lauder’s Learning from my Mistakes Lesson 10: Avoid head-hopping like the plague!

Suzan Lauder’s Learning from my Mistakes Lesson 10: Avoid head-hopping like the plague!

Both ON and Third Person Limited are third person voices. The main difference is that in Third Person Limited, the story is told in the voice of the character and not a narrator. Using the camera analogy, the camera is sitting on the shoulder of one of the characters, and is almost in their head. This is as close to first person as third person gets. In fact, you can write Third Person, Limited POV in first person then change to the person’s name or a pronoun to achieve this POV for each of your characters. Further limiting the number of characters with a voice, this POV should have no more than four lead POVs, and Lesson 10 is imperative, not just a great idea.

Many Romance novels use only the voices of the hero and heroine, and change them by chapter. I recently read a novel by mature Regency romance author Tessa Dare where the character’s voice changed within a chapter; however, she used an extra line break to signal the reader to the change in POV speaker within a scene. I prefer changing only by scene and using a section break or scene separator, which is a graphic like a curlicue, to show this change within a chapter.

Suzan Lauder’s Learning from my Mistakes Lesson 11: To avoid a choppy or head-hopping effect within a chapter, use an extra line break, a graphic section break, or a scene separator when changing point of view.

Suzan Lauder’s Learning from my Mistakes Lesson 11: To avoid a choppy or head-hopping effect within a chapter, use an extra line break, a graphic section break, or a scene separator when changing point of view.

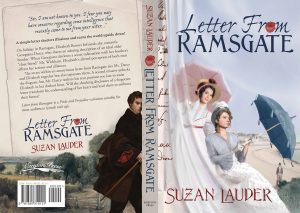

In the initial draft of Letter from Ramsgate, I’d used Deep POV with four characters and section breaks for all character POV changes, but had a longer section where I showed reactions of all the characters in the scene, including a minor character, and had it as one section. My anonymous beta editor suggested that I cut those who were not main POV characters and reword so the information could be told by a main POV character.

A good way to discover which POVs are important is to put in the section breaks as per Lesson 11 through one chapter that’s busy with characters. This will show the choppy head-hopping sections, encourage the author to change the story to reduce unnecessary POVs, and help set a direction as to what is the most important information to retain. It’s always possible to find a way to reveal a non-POV character’s motivation and character without “telling” it.

Deep POV

A further enrichment of Third Person Limited, the great advantage to Deep POV is the reader is so close to the character, they almost feel as if they are in the story, and a more profound effect results. I recall the first time I read this style. It was a novel by author Catherine Gayle with a hilarious and very realistic virginal sex scene from the female protagonist’s POV. It was such amazing writing, I wanted to write like her and wanted to know how to do so! I thought it was just Catherine Gayle’s personal style until I read Jill Elizabeth Nelson’s Rivet Your Readers with Deep Point of View from a recommendation by MP author Karen M. Cox.

Deep Point of View is achieved with a character-driven story with tight characterization, a minimum of POV characters (usually two), a lack of filter words, a “show, don’t tell” style, and a certain amount of introspection, though care must be taken not to overdo this latter aspect.

What are filter words? Because the story is being told by the character and not the ON, there is no “He thought, knew, felt, saw, smelled, heard, wondered, pondered, etc.” The character just does these things without thinking. The author is challenged to show, not tell, these filter words, as in Lesson 9.

Suzan Lauder’s Learning from My Mistakes Lesson 12: Change filter words of thought, feeling, and senses to make the POV deeper and enhance the reader experience.

Suzan Lauder’s Learning from My Mistakes Lesson 12: Change filter words of thought, feeling, and senses to make the POV deeper and enhance the reader experience.

This useful article by Jodie Renner covers many of the main points of Deep POV. Deep POV is not just for third person, but can also be used to enhance first person writing.

First Person

This is the “I” POV. Not much else to say, except you’re stuck with one character’s eyes through the entire story.

I thought I’d never use this until I started writing A Most Handsome Gentleman (my latest novella, in editing for publication by Meryton Press this fall) and it just came out of me that way. I had a lot of fun with it, and it worked well for a comedy!

Many famous books use this POV, but for some reason, a certain number of readers don’t much care for it. It can be difficult if the author wants to sneak in a second person’s POV, but it’s always possible to do excellent characterization and motivation of another protagonist through a first person narrator’s eyes, as is done routinely in Young Adult and New Adult writing these days.

As noted, deep POV can be used for first person—just eliminate those filter words as in Lesson 12 above.

Mixed POVs

One of my earliest A Happy Assembly stories Performing to Strangers mixed first person and ON, and separated them by scene. In the ON scenes, the POV was clearly the male protagonist, and the female protagonist was in the first person scenes. It was a moderate success, with a bit of reader confusion. That’s why many experts recommend against switching from one style to another in a story. Changes in POV style are not recommended and if done, section breaks are even more necessary than with the POV character changes.

A slight exception is Deep POV, where it’s permissible to break up the depth by brief ON scene setting every so often at the start of a scene. A scene in Letter from Ramsgate was about to be told by Georgiana, but first, I described the guests at Pemberley as they lazed on the lawns. I tried to make it seem like Georgiana’s POV until I read about this exception. It could easily have been her thoughts or a camera high in the sky, but the generalized tone broke up the heaviness that can come with being in one head at a time for long time periods. It was one short paragraph, then I zoomed tight for her POV.

I read a JAFF novel where the bulk of the story was in ON, then all of a sudden, the author had gone into the character’s thoughts, using an introspective type of style different than the bulk of the novel, and head-hopped while doing this, without enough cues as to who was doing the thinking. I was jarred and had to go back to re-read.

Suzan Lauder’s Learning from My Mistakes Lesson 13: Be consistent with your POV selection.

Suzan Lauder’s Learning from My Mistakes Lesson 13: Be consistent with your POV selection.

How to Choose?

With several main POV types to use and four rules suggested by my experience in writing and reading, an author can be overwhelmed in deciding which is best for their story. Sometimes the easiest style is not the best for your readers, and you have to work for good communication. Sometimes you have to be consistent with the genre in which you are writing. For example, Third Person Limited, Deep POV, two speakers (male and female protagonist) is best in most romance novels, though hipper subgenres such as New Adult and Chick Lit utilize first person a great majority of the time. Sometimes, like in my experience with A Most Handsome Gentleman, the choice is easy.

There are tons of articles touting one POV over the other, and a lot of what you’ve read in this one may assist you. However, if you’re still unsure, check out this excellent article by Janice Hardy that explores the pitfalls of each POV.

Of course, there are exceptions to everything, and many famous authors have achieved success with exceptions. But when you think you can be the exception, ask yourself: are you truly as talented as that Pulitzer-Winning author? A reply of “yes” is rather bold. Don’t be caught as a diva by kidding yourself in your vanity! The rules are made for us “regular” authors who love to improve our craft and don’t ever sit on our laurels and say we’re the best.

Have fun picking your POV!

Disclaimer: I’m not a writing expert. I’m just a writer who learned some stuff other writers might like to know instead of learning the hard way. My approach is pragmatic, and my posts are not professionally edited!

Save