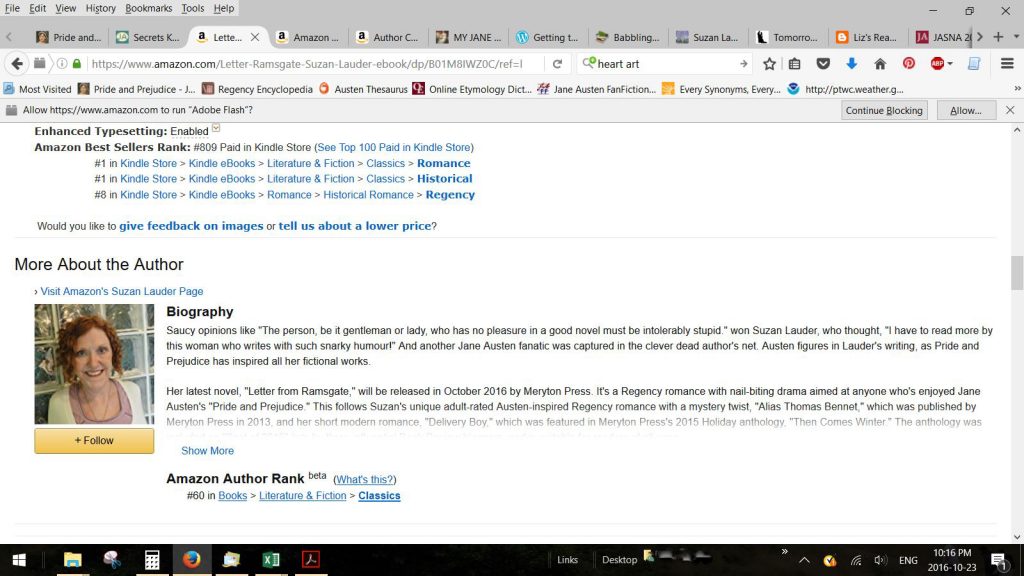

I said in an earlier post that I’d share my list of words to search for if you want to un-muddy your writing to help you self-edit. (Lesson #2 and #3 at end of post). This list is a golden gem of mine that started after I read a book called Editor-Proof Your Writing by Don McNair. I’ve used the ideas he suggested in the book and added many of my own to create a list of 100 words to search for to improve your writing.

“100 words?” you ask, “Isn’t that tedious?”

Yes it is. And if you don’t use these words, or get in the habit of it after having searched for the 100 a few times, your writing will shine. It’s worth tedium of a few rounds to get better as a writer. In addition, if you, like may authors, want to shave some word count off your novel, this review can often cut 5% of word count at first. Yes, my writing was 5% muddy before it ever got to an editor!

My over-used words at one point or another: that, look, act, then, such, all, as, about, turned, smile, scowl, however, in fact. What are yours?

But there’s more: I like to pare down adverbs to the minimum by rewording (including considering the adverb as the verb or adjective instead) or cutting, but I don’t believe in removing them totally, as they do have their purpose. A good rule of thumb is an average of no more than one -ly adverb per page of text. Adverbs like really, totally, only, and just can almost always be cut.

There are words I’ve taught myself to limit use, and the top of that list is another adverb: very. Most of the time, this adverb is your story begging for a better adjective. Very small: diminutive. Very old: antiquated. Very pretty: beautiful. Very late: tardy. Very lazy: lackadaisical. You get the idea. Get to be friends with a good thesaurus for better word use.

There are words I’ve taught myself to limit use, and the top of that list is another adverb: very. Most of the time, this adverb is your story begging for a better adjective. Very small: diminutive. Very old: antiquated. Very pretty: beautiful. Very late: tardy. Very lazy: lackadaisical. You get the idea. Get to be friends with a good thesaurus for better word use.

Some word formations can signal passive tone, such as a verb ending in –ed with to, or some –ing words, or had with another verb. Keep it active.

If you want to be a good POV (point of view) writer in third person deep point of view, you must get rid of “filter” words. More on that in a POV post, but I mention it because it’s on the cheat sheet.

If you’re like me, and write period fiction, you’ll also want to find words that were not in use during the period and exchange them for something more appropriate to the times. For example, the word “high-tech” is from the 1970’s, so you don’t want it in your Second World War story or older. Since I write Regency, I’ll have a post on Regency language later in the series.

How to use the checklist? In MS Word, there’s a function called “Find” on the “Home” tab. Type in the letters of the checklist item, then use the arrows in the pop-up box to go from one to the next. Evaluate each case, and if needed, reword, watching not to get into the rut of using another muddy style. You don’t have to change them all, just the ones that are easy to change. Soon, you’ll recognize your style and which words are never a problem for you.

After using the list a few times, you’re bound to customize the 100-word list for yourself, adding words your beta reader has indicated are over-used and crossing off those you have no issues with. These change from time to time, so be flexible with your checklist.

Suzan Lauder’s 100 word Editing Checklist

The applicable lessons to this post:

Suzan Lauder’s Learn from My Mistakes Lesson #2: Several full author edits are the preferred norm for ensuring quality writing.

Suzan Lauder’s Learn from My Mistakes Lesson #2: Several full author edits are the preferred norm for ensuring quality writing.

Suzan Lauder’s Learn from My Mistakes Lesson #3: Keep a checklist of your most common errors and use a “Find” function to clean them up during your later editing process.

Suzan Lauder’s Learn from My Mistakes Lesson #3: Keep a checklist of your most common errors and use a “Find” function to clean them up during your later editing process.

I hope a few of you share some words that would be on your list in the comments for this post. Enjoy your self-editing experiences!

~~~

Please note the new widget on the right panel of my blog main page at the bottom. It takes you to my newest story posting for free at AHA, A Most Handsome Gentleman (formerly known as “Hot Collins”). It’s funny!

Save